Bladder Stones

Urolithiasis Urinary Tract Stones and Bladder Stones

Urolithiasis is a condition arising from the formation of renal calculi when the urine is supersaturated with salt and minerals such as calcium oxalate, struvite (ammonium magnesium phosphate), uric acid and cystine [1]. 80% of stones contain calcium [2] . These urinary tract stones vary considerably in size from small 'gravel-like' stones to large staghorn calculi. The calculi may stay in the position in which they are formed, or migrate down the urinary tract, producing symptoms along the way. Studies suggest that the initial factor involved in the formation of a urinary tract stone may be the presence of nanobacteria that form a calcium phosphate shell [3, 4].

The other factor that leads to urolithiasis/urinary tract stone production is the formation of Randall's plaques. Calcium oxalate precipitates form in the basement membrane of the thin loops of Henle; these eventually accumulate in the subepithelial space of the renal papillae, leading to a Randall's plaque and eventually a calculus [5].

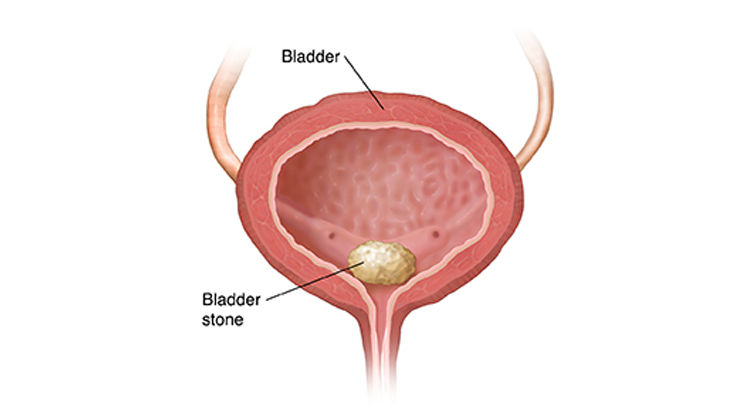

Bladder stones

Bladder stones (calculi) account for around 5% of urinary tract stones and usually occur because of foreign bodies, obstruction or infection [6]. The most common cause of bladder stones is urinary stasis due to failure of emptying the bladder completely on urination, with the majority of cases occurring in men with bladder outflow obstruction[7]. Approximately 5% of bladder stones occur in women and are usually associated with foreign bodies such as sutures, synthetic tapes or meshes, and urinary stasis, so bladder stones should always be considered in women investigated for irritable bladder symptoms or recurrent urinary tract infections [8].

Patients with indwelling Foley catheters are also at high risk for developing bladder stones and there appears to be a significant association between bladder stones and the formation of malignant bladder tumours in these patients.

Risk factors

Several risk factors are recognised to increase the potential of a susceptible individual to develop urinary tract stones or urolithiasis. These include:

- Anatomical anomalies in the kidneys and/or urinary tract - eg, horseshoe kidney, ureteral stricture.

- Family history of urinary tract stones. Stone formation is twice as likely to occur in people who have a first-degree relative with stones.

- Hypertension

- Gout

- Hyperparathyroidism

- Immobilisation

- Relative dehydration

- Metabolic disorders which increase excretion of solutes - eg, chronic metabolic acidosis, hypercalciuria, hyperuricosuria

- Chronic lead and cadmium exposure are associated with stone formation.

- Deficiency of citrate in the urine.

- Cystinuria (an autosomal-recessive aminoaciduria).

- Drugs - eg, diuretics such as triamterene and calcium/vitamin D supplements.

- More common occurrence in hot climates, due to the effect on fluid status and urine volume.

- A diet with excessive intake of oxalate, urate, sodium, and animal protein.

- Increased risk of stones in higher socio-economic groups.

- Obesity - the association seems to be greater in women than in men. It is thought that low urine pH and uric acid stones and an association with hypercalciuria could account for an increased risk of uric acid and/or calcium stones in obese people.

- Contamination - as demonstrated by a spate of melamine-contaminated infant milk formula [9].

Risks for recurrent stone formation include:

- Type of stone - people with calcium-containing stones, uric acid and ammonium urate stones, and infection stones (such as struvite stones).

- Positive family history of stones.

- Previous stone formation.

- Early onset of stones.

Presentation of complaints of the patient: [2]

- Many urinary tract stones are asymptomatic and discovered during investigations for other conditions.

The classical features of renal colic are sudden severe pain. It is usually caused by stones in the kidney, renal pelvis or ureter, causing dilatation, stretching and spasm of the ureter. In most cases no cause is found:

- Pain starts in the loin about the level of the costovertebral angle (but sometimes lower) and moves to the groin, with tenderness of the loin or renal angle, sometimes with haematuria.

- If the stone is high and distends the renal capsule then pain will be in the flank but as it moves down pain will move anteriorly and down towards the groin.

- A stone that is moving is often more painful than a stone that is static.

- The pain radiates down to the testis, scrotum, labia or anterior thigh.

- Whereas the pain of biliary or intestinal colic is intermittent, the pain of renal colic is more constant but there are often periods of relief or just a dull ache before it returns. The pain may change as the stone moves. The patient is often able to point to the place of maximal pain and this has a good correlation with the current site of the stone.

Other symptoms which may be present include:

- Rigors and fever.

- Dysuria

- Haematuria.

- Urinary retention.

- Nausea and vomiting.

Management [2, 12]

Initial management of urolithiasis or urinary tract stones can either be done as an inpatient or on an urgent outpatient basis, usually depending on how easily the pain can be controlled.

Indications for hospital admission

- Signs of systemic infection - eg, fever, sweats, sepsis.

- Increased risk of acute kidney injury - eg, solitary kidney, known non-functioning kidney, transplanted kidney, suspected bilateral renal stones.

- Inadequate pain relief or persistent pain.

- Inability to take adequate fluids due to nausea and vomiting.

- Anuria.

- Inability to arrange imaging within 24 hours.

- Diagnostic uncertainty..

For all other patients, offer urgent imaging

Surgical

- If the pain cannot be tolerated or the stone is unlikely to pass, surgical treatment should be considered for adults with ureteric stones and renal colic within 48 hours of diagnosis or readmission. The choice of procedure depends on such factors as the size of the stone, the person's age, contra-indications, a history of failed previous procedure, and anatomical considerations.

Options include:

- Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) - shock waves are directed over the stone to break it apart. The stone particles will then pass spontaneously.

- Percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL) - used for large stones (>2 cm), staghorn calculi and also cystine stones. Stones are removed at the time of the procedure using a nephroscope.

- Ureteroscopy - this involves the use of laser to break up the stone and has an excellent success rate in experienced hands.

- Open surgery - rarely necessary and usually reserved for complicated cases or for those in whom all the above have failed - eg, multiple stones.

- Several options are available for the treatment of bladder stones. The percutaneous approach has lower morbidity, with similar results to transurethral surgery while ESWL has the lowest rate of elimination of bladder stones and is reserved for patients at high surgical risk [7].

Results

- It has been calculated that 95% of ureteral stones up to 4 mm pass within 40 days.

- Stones between 5 mm and 10 mm in diameter pass spontaneously in about 50% of people.

A systematic review found that [16]:

- 64% of people spontaneously passed their stones: approximately 49% of upper ureteral stones, 58% of mid-ureteral stones, and 68% of distal ureteral stones were successfully passed.

- Almost 75% of stones less than 5 mm and 62% of stones 5 mm or more passed spontaneously.

- It took about 17 days for stone expulsion to occur (range 6–29 days).

- Nearly 5% of participants required re-admission to hospital because their condition had deteriorated.

- Recurrence in people who have not had previous stones is 50% at five years and 80% at 10 years.

Prevention

Recurrence of urinary tract stones like renal stones or bladder stones is common and therefore patients who have had a renal stone should be advised to adapt and adopt several lifestyle measures which will help to prevent or delay recurrence:

- Increase fluid intake to maintain urine output at 2-3 litres per day.

- Add fresh lemon juice to drinking water and avoid carbonated drinks.

- Reduce salt intake.

- Eat a healthy diet and maintain a normal weight.

- Do not restrict calcium intake.

Depending on the composition of the stone, medication to prevent further stone formation is sometimes given:

Consider potassium citrate for:

- Children and young people with a recurrence of stones that are mainly (more than 50%) calcium oxalate, and with hypercalciuria or hypocitraturia.

- Adults with recurrent stones that are mainly (more than 50%) calcium oxalate

- Consider thiazide diuretics for adults with a recurrence of stones that are mainly (more than 50%) calcium oxalate and hypercalciuria, after restricting their sodium intake to no more than 6 g a day.

- A stapler circumcision is performed for all the routine causes for a circumcision {provide link to circumcision literature}

- A Stitchless(Stapler) Circumcision is superior than routine circumcision because it has negligible bloodloss and only 10% of the pain than what patient has to face in a stitched circumcision

- Healing time is much faster and our patients join routine within a period of 1-2 days compared to 7-10 days after a stitched circumcision.

- Only 1 post-operative required and no further need for any dressings. Staplers fall off automatically.

- v. Ideal weak end surgery, where the patient can get operated on Saturday and return to work on Monday without any untoward pain or difficulties.